Newsweek [International Version 12/1/97]

Newsweek [International Version 12/1/97]

Bikini Atoll's Blue Lagoon

By Jeffrey Bartholet

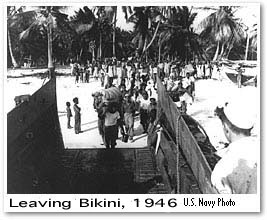

Bikini isn't just a synonym for a skimpy little bathing suit. It's also the name of a remote Pacific atoll that served as the site for 23 U.S. nuclear tests, including atomic- and hydrogen-bomb explosions, between 1946 and 1958. Bikini's inhabitants, numbering 167 at the time, were moved to another island before the first A-bomb went off there. Some families returned in 1969 but had to be evacuated again because of lingering radioactive contamination. Bikini is perfectly safe for visitors, however, and now the word is out: the atoll with the ubiquitous name offers some of the most spectacular scuba diving anywhere in the world. Jack Niedenthal, a native of Pennsylvania who married a Bikinian islander and has lived in the area for 17 years, works as an advisor to the Bikinians and represents their interests to the outside world. Newsweek's Jeffrey Bartholet spoke to Niedenthal, 39, at his office on Majuro Atoll, which like Bikini is part of the Marshall Islands. Excerpts:

BARTHOLET: What's diving like at Bikini?

BARTHOLET: What's diving like at Bikini?

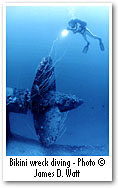

NIEDENTHAL: In a one-week visit you can do 12 dives. They are very exhausting and long dives. It's like going to the moon twice a day.

BARTHOLET: What do you see?

NIEDENTHAL: The ships destroyed by the "Able" and "Baker" blasts of July 1946. The navy wanted to see what it would be like to drop an atomic bomb on a fleet at sea. So they arranged the ships just as though they were going into battle. They had goats on the decks to simulate human beings. The planes all have their wings [folded] with bombs on the racks.

BARTHOLET: Which ships are the favorite dive sites?

NIEDENTHAL: The Nagato was the flagship of Admiral Yamamoto--the man of "Tora! Tora! Tora!" fame. That's the ship he was on when he ordered the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was his floating fortress. It's upside down now and looks like an underwater view of Stonehenge. So eerie looking. The aircraft carrier Saratoga is there, too. The Japanese thought they had sunk it six or seven times during the war. A lot of servicemen who served in World War II like to dive it.

BARTHOLET: How many people have done the dive so far?

BARTHOLET: How many people have done the dive so far?

NIEDENTHAL: Last year we had 100 people. It doesn't sound like a lot. But to get 100 people to a remote location like Bikini is not easy. This year we expect to have a total of 160. For the Bikinians, it's not so much the money that's important, but the chance to tell their story to more and more people.

BARTHOLET: In a nutshell, what is their story?

NIEDENTHAL: The Japanese were here before the Americans, and they convinced everyone that they were the rulers of the universe. Then the Americans came and beat the rulers of the universe. Then these new rulers asked the Bikinians: "Is it OK if we use your island to test some weapons?" The Bikinians felt they had no choice. They were moved to Rongerik atoll, where no one had ever lived. There was a reason no one had lived there: the fish in the lagoon were toxic. The second reason was that, according to traditional beliefs, the fish were poisonous because the lagoon was inhabited by demons. For two years the people starved. Then they were taken to Kwajalein atoll and lived there in tents for about six months.

BARTHOLET: Where did they go next?

BARTHOLET: Where did they go next?

NIEDENTHAL: They decided on Kili island, because it was uninhabited and not ruled by a paramount king. There wasn't enough food. But they thought they'd have more political freedom. They went there and basically had a very hard time for 40 years. Finally, they got some attention from the media. They filed lawsuits, got some trust funds in place. There are three different trust funds now.

BARTHOLET: Is Bikini safe enough to live on now?

NIEDENTHAL: In 1968 President Johnson declared that Bikini was safe. Three old men and their families went back. By 1978 it was discovered that some of the people on Bikini had radiation levels well above the U.S. maximum permissible levels. Now they live on Ejit island.

BARTHOLET: What's the situation now?

NIEDENTHAL: Scientists say that if you spread potassium over the land, it will block the uptake of cesium-137, the radioactive element, and people will be able to resettle. But to the Bikinians, it looks like 1968 all over again. We're now clearing the land to get ready to scrape it and spread the potassium. But there's no movement of the people yet.

BARTHOLET: What is the total population of Bikinians?

NIEDENTHAL: The most recent figure is 2,372.

BARTHOLET: How many might return?

BARTHOLET: How many might return?

NIEDENTHAL: That's the $64,000 question. Everybody will go back, some for a short visit, others for a long time. But you won't see 2,000 people jump on a big ship and sail home to live. It's not conceivable that they'll go back to living the way they were. They're part of the modern world now. Still, people who want to go back will have a chance to tie in to the industry we're creating there. Diving, and also fishing. It's a place where no one has lived for 50 years. The whole place is just teaming with fish. Where in the world can you be the only guy standing on miles of white-sand beach, with a blue lagoon and a blue sky? There's a whole aura about the place you won't find anywhere else. It's the main reason the U.S. government chose it to begin with as a place to test atomic weapons. It's so remote. It's very out there.

ABC World News Now interview with Jack Niedenthal.